The ‘interconnected’ approach to law is a relational approach. This means that it understands humans as relational beings, recognises the way that law affects these relationships, and frames law’s objective(s) in a relational way.

This article is heavily influenced and draws from Jennifer Nedelsky’s book Law’s Relations: A Relational Theory of Self, Autonomy, and Law. I did not cite or footnote particular passages, instead wanting it to read as a stand-alone instead of a commentary, but significant credit to her work.

Humans as relational

Our main political and social worldview sees humans as individuals, society as a collection of individuals, and politics as the competing wants, needs and rights of these individuals. The liberal tradition – dominant in philosophy and law for hundreds of years – has its starting point as the individual person, conceptually abstract from others, and constructed social theories based on this individualised conception.

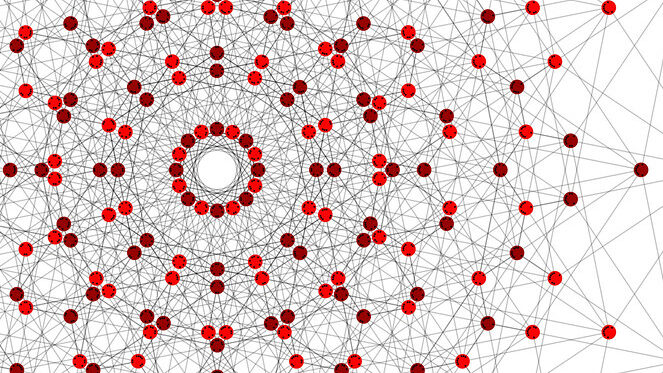

Yet this is not who we are. No-one is an island. Instead of living as individuals who occasionally interact with others, we instead live in a network of relations and relationships.

We have our social relationships, from those we are close to through to our neighbourhoods, communities and society. We have economic relations, such as with employers, businesses, corporations, and political relationships. And we have relationships with Nature, our environment, such as with forests, local parks, ecosystems, the places from which we get food, and the temperature of our planet.

While we are individuals, we live in all of these relations and relationships.

These relationships can be positive, such as nurturing social relations, education, just employment and an environment which gives physical conditions for us to thrive. Or they can be negative, such as abusive interpersonal relationships, exploitative work relationships, racist and sexist social relations, or environments which are toxic to us.

A relational approach is about understanding the individual in the dense network of relationships which constitute us and have a huge impact on our lives, and about understanding society as being this network of relationships in which everyone lives.

To be clear: ‘relationships’ is meant broadly in this article, not only interpersonal relationships but any sort of relation in society. This could include relationships such as the person reading this and a tree that they occasionally see out their window, though that would be a very weak relationship.

Law’s Role in This Network of Relations

Turning to law, the point is not that law should do something about this – it is that law already does do something about this.

Our legal systems already structure and influences many of our relationships. Not alone, of course, but they are certainly a significant part of it.

Our legal systems designate Nature as simple objects, as property which humans can plunder, or occasionally it designates particular places or ecosystems as being somehow protected. It gives employees certain minimum rights against their employer, while also giving employers the remaining freedom of action to treat employees as they wish outside these limits. We all interact with each other against a background of criminal and civil law, which expects certain things of us and may intervene or punish if any of these norms are transgressed.

There are relationships which are particularly mediated by law, such as relationships like marriage, partnership and divorce, and deciding what is in a child’s best interests. There are also relations where law is a bit more in the background, but still there, such as a child’s relationship with the school system, where children are forced to attend school with little say themselves, or like rights people have from the state, such as social security or access to housing.

Relationships between people and places are controlled by the law, such as who can go where, where skateboarders can skate, whether people in specific parks can climb trees, and whether protests are allowed (or in what way). This also includes border regimes and the entire immigration system.

In these relationships, law can be positive or negative. It might help structure a positive relationship, or it might create or leave space for harmful relationships.

In employment law, protection against discrimination or unfair dismissal give some level of security, and minimum wage laws affect pay. Union rights also exist to either facilitate or limit collective bargaining and campaigning, and law could, for example, require workers to have some say in how the company is run and how the profits are distributed.

In interpersonal relationships, law continues to perpetuate gender inequality. Law used to do this in quite obvious ways by not allowing women to own property, or through a lack of agency given to women in marriage. While formal legal equality has now, for the most part, been established in the UK, there are still ways within legal systems or state apparatus that perpetuate gender inequalities. Universal Credit, for example, is paid to couples instead of to individuals, which creates difficulties for someone who might wish to leave their partner. Similarly, the right to safety and security is mostly the liberal negative right to protect someone from others, instead of to provide them with what they need to be safe and secure. Somebody who wishes to leave an abusive or dangerous relationship cannot easily go to the state to house them and feed them and help them to re-establish themselves; this is typically done by friends, family or charities, with a mixed response from police protection.

Immigration law in the UK is an example of a way in which law creates conditions in which exploitative relationships can thrive. Many migrant workers are reliant on the job they do to be able to stay in their country, through a system of ‘employer sponsorship’. This means that the employer knows that if the employee loses their job, they may have to leave the country, which is a bigger threat to have hanging over someone than just their livelihood depending on their work. The criminal offences of ‘illegal working’ mean that people without regular immigration status can be exploited, because the employer knows that the employee is unlikely to report sexual assault or wage theft because the employee is themselves committing a criminal offence and liable to be deported.

Property law allows landlords to extract money from people who do not (and cannot afford to) own property, and can make them homeless if they become unable to pay. A wealthy person who owns multiple houses is empowered by the law to prevent anybody else from accessing one of their houses, even if it is empty and even if the homeless person is in serious danger if they stay outside.

Law is not, of course, the only thing which affects relationships throughout our society. Economics, politics, particular state policies, culture, morality and personality are also a part of it. These are all interwoven, despite how we often conceptualised them separately: our legal system makes our economic system possible, and our social norms heavily influence our legal systems and legal norms, which in turn reinforce and perpetuate those social norms.

The point here is only that law does have a significant effect on relationships within its domain, not that it is the only thing. But it must be remembered that all of these are interwoven: law and culture influence and reinforce each other, law affects economics, law helps us form ideas of who we are in relation to other people, and so on.

Law as Relational

As well as recognising the way that law affects relationships in society, it should also

be recognised that it is inherently relational too. Law is about governing relationships between people, places, animals and other beings and things.

I don’t know the extent to which this is obvious, as it now seems it to spell it out like this, but having studied law for a few years, when I first read about the relational approach to law it was a revelation. Writing this now, it seems like this is obvious to everyone and pointless to set out, but something tells me that this may not be the case – you can let me know your thoughts.

Even a crude Hobbesian notion of law – that without law and the state existing, we would all be running around killing and stealing from each other, which would be quite bad – posits law and in particular criminal law as existing to mediate relationships between individuals by providing personal security and protecting private property.

As described above, it is inherent to law to be mediating relationships.

‘Law as regulation’ is also about relationships, setting a framework or minimum standards for how people treat each other, such as health and safety law as a framework between employers and employees, consumer protection as a framework between sellers and consumers, or coronavirus guidelines obviously setting a framework within which we all act.

Although we think, fundamentally, about rights, the point of a right is to set a certain expectation or bring about a certain outcome vis-a-vis the person the right acts on. In a contract, it’s about the performance of the contract, a certain outcome the other person(s) in the relationship must bring about. Property right is about everyone else who must respect the property right. And so on.

Human rights is also fundamentally relational, though when studying it I never noticed this explicitly recognised anywhere. I will write more about this in a separate post, but the summary is that human rights are quite broad, eg privacy, so as a framework it sets up there to be lots of rights-conflicts. Human rights decision mitigation or legal processes are therefore about resolving rights conflicts, which is about the relationship between the rights-holders.

What does this all mean for law?

Once we recognise that humans live in a network of relationships, social and otherwise, and that law is part of structuring this, we can now ask the question: what does this mean for law?

One part of the answer to this is around our understanding and conceptualisation of law and legal systems. Our understanding of individuals, society, the state, politics and law should be updated to reflect this relational understanding. This can seem like a small shift, that we need to think about relations instead of just individuals, but it is quite a significant shift too, a revolution in our worldview to give relationships the same primacy that we give individuals.

Based on this understanding, there is a second point that law would work better in achieving whatever ends it is put to if it recognises the relational nature of our society and of individuals, and law’s own relational nature.

The shift in emphasis should completely change legal and political thought, a complete paradigm shift for how we understand law, how we structure legal systems and policies about legal systems.

Those are both formal, or neutral points: that our understanding and use of law would be better if it had this better understanding. This article was written in a fairly neutral or descriptive way to make those points. But going beyond these formal points, we should also think normatively about the goals and purposes of law, and how it relates to justice and realising a better world. I have written more about this here.